When I was in graduate school at SVA, I was able to choose an advisor during my thesis year. My choice was Pat Cummings. I asked Pat because I had been reading her books and admiring her art since “Just Us Women” appeared on Reading Rainbow in 1984. I went on to fall in love with C.L.O.U.D.S. and fueled my passion for breaking into the field with her “Talking with Artists” series. Not only has Pat been a great role model through her work and life, she has also been an amazing mentor and friend. I sent a few questions her way to host our conversation here on Living the Dream. Initially I hoped to do a video chat and post it to my Youtube channel, so in lieu of that live conversation, I will insert a few footnotes here and there, à la Junot Dìaz. Without further ado, Pat Cummings.

When I was in graduate school at SVA, I was able to choose an advisor during my thesis year. My choice was Pat Cummings. I asked Pat because I had been reading her books and admiring her art since “Just Us Women” appeared on Reading Rainbow in 1984. I went on to fall in love with C.L.O.U.D.S. and fueled my passion for breaking into the field with her “Talking with Artists” series. Not only has Pat been a great role model through her work and life, she has also been an amazing mentor and friend. I sent a few questions her way to host our conversation here on Living the Dream. Initially I hoped to do a video chat and post it to my Youtube channel, so in lieu of that live conversation, I will insert a few footnotes here and there, à la Junot Dìaz. Without further ado, Pat Cummings.

Pat, you have been illustrating books for over 30 years now. My first memory of your work was in the Reading Rainbow Book, Just Us Women. You were one of the only people of color on my radar who made books about children of color that were more whimsical and didn’t solely focus on history. Can you talk to me a bit about how you entered publishing and the motivation behind the books that you have created?

I had been to see a bunch of publishers, not realizing that seeing one editor at a publishing house did not mean you’d really covered the whole house. So it had been hit and miss. There was a newsletter back then (this was the early/mid seventies) published by The Council on Interracial Books for Children. They highlighted an illustrator or photographer on their back page. When they ran my work, an editor at one of the publishing houses I thought I had covered called me and said she had a book for me. I had NO idea how to start but I didn’t want to let on that I was clueless. So I did what seemed reasonable. I knew someone who knew someone who knew someone who had once dated Tom Feelings. So I called him up, explained my situation and he took the time to walk me through how he put a book together. He was working on The Middle Passage. It was 1975. That book came out in 1995. He was my hero when it came to deadlines.1 (Be kind, Shadra.)

Has there been any time in your career where you wanted to stop writing and illustrating books? If so, what kept you going?

Nope. There have been times I wanted to stop drawing and just write. But not permanently. I just wanted a change of pace. There are too many stories I’d like to get to so I can’t imagine NOT wanting to tell them.

You work closely with SCBWI, The Highlights Foundation, and The Author’s Guild. How does this work inform your book making?

You work closely with SCBWI, The Highlights Foundation, and The Author’s Guild. How does this work inform your book making?

I was actually someone who was anti-groups when I was in college. It took me a while to realize that others had invented the wheel already. When I had thanked Tom Feelings profusely for helping me, Tom said, ‘Just help someone else when you can.’ I took that to heart. I joined the Graphic Artists Guild and later, SCBWI. I found that anytime I shared something I had learned about the business, I invariably learned more. Every organization I work with, The Authors Guild, SCBWI, The Eric Carle Museum, Highlights, The Ezra Jack Keats Foundation…all of these groups…are immersed in the children’s book business in different ways. So I’ve learned a lot about business, about the craft of making books and I get to constantly see the new work that is coming from puppies like yourself. (Please, Louise puts you about one book away from graduating from Puppy status).

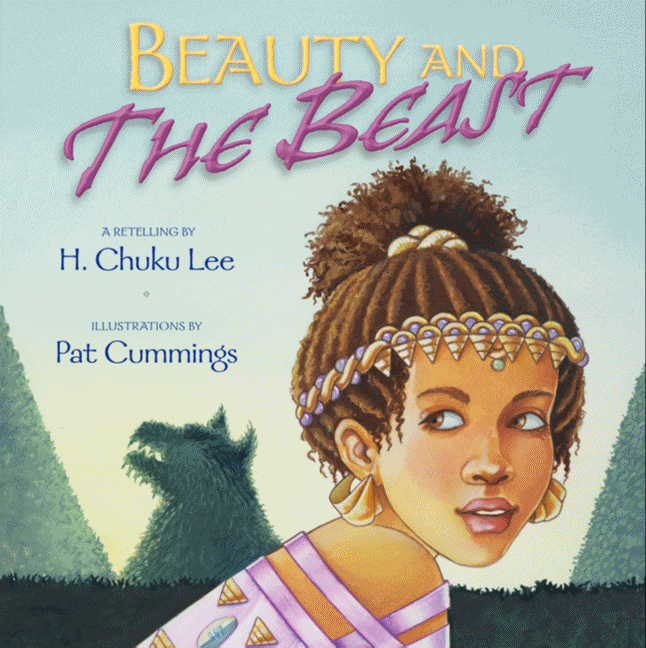

You just published a gorgeous version of “Beauty and the Beast” written by your husband, Chuku Lee. I first met Chuku in C.L.O.U.D.S., how was it working with him as a model to working with him as an author?

Why, thank you ma’am for the kind words. You know how long that book took to finish. Chuku used to be a magazine editor when I met him and he was doing cover interviews with folks like Muhammad Ali and Andrew Young. Aside from being a writer and editor, he had served in the Foreign Service as a junior office in Paris. So, when I found an original French version of Beauty and the Beast I wanted him to translate it and do the retelling. He wrote up the story and sent it in to our editor, Barbara Lalicki at HarperCollins. I warned him that the way it worked in publishing, he would have to crawl across hell over broken glass to get to a final version because editors were very exacting. But Barbara only asked for one minor change and then said, “It’s great.” I think the years of journalism paid off. Writing lean, mean text is the way to go these days and his retelling was elegant and lyrical. He has no idea how unusual his experience was.

As a model, he’s learned to be very patient and accommodating. I’ve had him standing on furniture at 3am so I can get an angled shot. As the author of the book he was a cheerleader and kept me motivated when I thought I’d never finish.2 Because this wasn’t his usual endeavor, he didn’t seem to feel any pressure about seeing the book finished. So he never mentioned that I was taking decades to get it done.

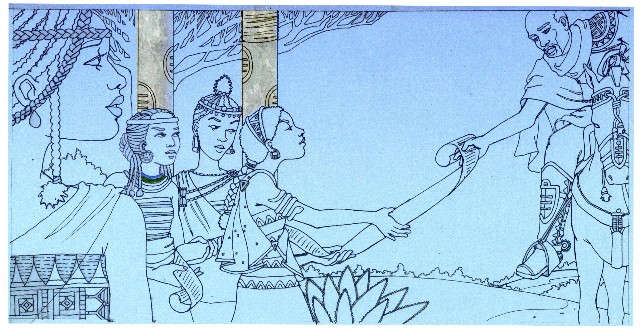

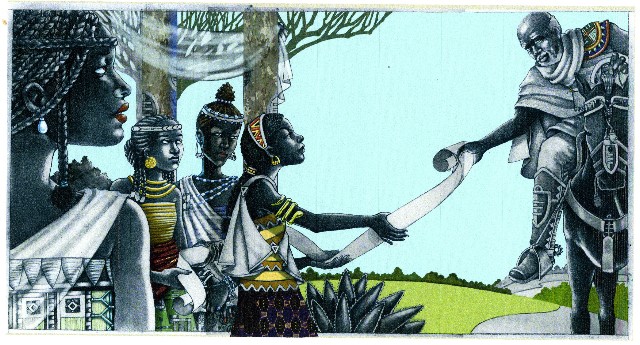

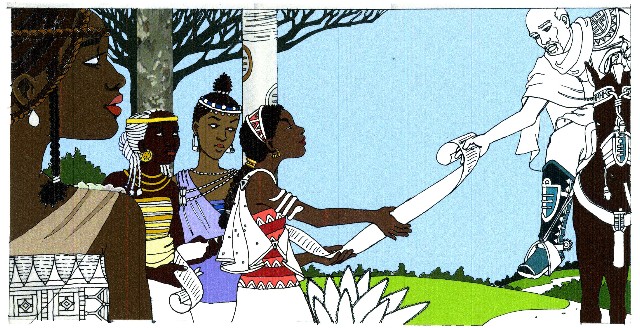

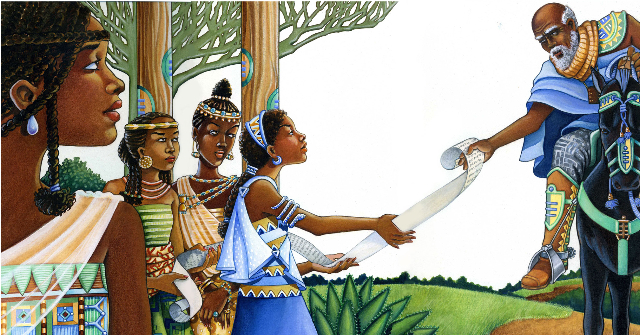

Can you talk a bit about the setting of the book? Why Africa and more specifically, Why Mali culture?

I’ve been fascinated by the Dogon for some time. Their masks and traditional costumes are graphic and richly colored. But, beyond any specific tribe, I’m attracted to the imagery of a host of cultures and West Africa was an ideal inspiration. I remember seeing the opening scene of Coming to America with Eddie Murphy. 3 A mythic African kingdom is depicted, very opulent and very Hollywood and I loved the idea of combining African imagery with a fairy tale theme. When I looked at the architecture of the Dogon, it held elements that I thought would be fitting for a castle where the Prince turned Beast might live. Along with the African inspiration though, I wanted to capture some of the mystery in the Jean Cocteau film version of Beauty and the Beast. I wanted to capture some of the magic in that film, with the watching faces in the architecture and waiting hands that provided whatever Beauty needed.

As a professor, you have mentored many successful illustrators, from David Ezra Stein, to Julian Hector, and myself, to name a few. You also take on a teaching role with SCBWI. How important is the work you do in the classroom? Do you consider teaching as much a part of your legacy as storytelling and being an artist?

You’r e a teacher so you must know how satisfying it is to be able to help others bring their stories to fruition. I think some people are genetically encoded to teach others and I recognize that in you. 4 When I told Tom that I would help others, I think I meant it sort of metaphorically. But I found it so satisfying to see projects come together and to see people start their careers that it truly became a large part of what I do now. I LOVE storytelling and I love just about every aspect of this business. So, when I see others who have the same passion for it, it’s pretty easy to encourage and help them connect to publishers. I feel proud of the folks I’ve worked with who have gone on to create wonderful books. But I can only advise. Their successes are all based on their unique talents.

e a teacher so you must know how satisfying it is to be able to help others bring their stories to fruition. I think some people are genetically encoded to teach others and I recognize that in you. 4 When I told Tom that I would help others, I think I meant it sort of metaphorically. But I found it so satisfying to see projects come together and to see people start their careers that it truly became a large part of what I do now. I LOVE storytelling and I love just about every aspect of this business. So, when I see others who have the same passion for it, it’s pretty easy to encourage and help them connect to publishers. I feel proud of the folks I’ve worked with who have gone on to create wonderful books. But I can only advise. Their successes are all based on their unique talents.

With someone like yourself, and all of you phenoms out of SVA….Taeeun Yoo, Lauren Castillo, Anna Raff, You Byun, Lisa Anchin…the list goes on, I remember having the impression that the future was crystal clear and right around the corner for you. When you start out, the problem with being in the trenches, working like crazy, is that it’s hard to see what’s ahead and it might feel like it could take forever. But to anyone like myself who has been in the business a while, talent glows in the dark. 5 So, I always remember how Tom Feelings helped me and I try to pass that on.

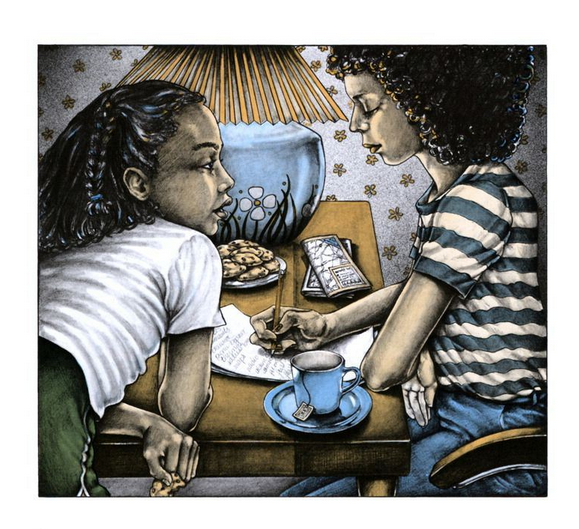

Can you talk a bit about your process? What are some of your favorite tools? What do you love the most about making art for picture books?

Eeeek. My ‘process’ is pretty much a hot mess. I doodle for days. I collect the doodles, compose a slew of layouts, discard half and put together a smorgasbord of images to discuss with my editor. Usually, I feel my way along a dark corridor, downloading images from dreams, things I’ve seen, music, travels….doodling and then, refining the doodles. Eventually, I pick variations, stick them into mini dummies and then blow them up to refine further. I go through about three or four dummies at least. 6 When I have layouts I like, I start final drawings in whatever order appeals. Those final drawings are done by hand but in a photoshop, layer fashion: a hand here, a horse there, a house on yet another piece of trace paper. I assemble all of the scraps on my drawing table where I’ll have drawn an outline of the open book. After I’ve arranged the various elements within that frame, I put a piece of trace paper over everything and make a final ink drawing. That drawing I copy onto Fabriano Artistico hot press paper, the heavy stuff….300 pound I think. I use paper that is forgiving because I tend to abuse it.

With the drawing done in light pencil (usually 3 or 4H), I usually do washes of the background colors or any underpainting first. Then I feel my way along in terms of color. If I’ve put down an olive green, I might feel I need a rust next to it. Even if I’ve done color studies, I tend to just go with my gut once I start painting. It surprises me without fail, that after the book is done I’ll see there was a particular palette specific to the book. Only rarely have I set out with an intentional palette. I use watercolor and gouache pretty interchangeably, go in with color pencil, smooth things out with pastel, hit it with anything that seems called for and then spray the whole thing heavily. I don’t recommend this. What I do know is that I may start a page with every intention of being light and washy and loose and then things get brighter and juicier and tighter and I swear that the next book will be light and loose.7

The #WeNeedDiverseBooks Campaign has been a hot topic for a few weeks now. As a maker of diverse books for children and a luminary in the field, what are some of your thoughts on this issue?

The percentages haven’t changed since I’ve been doing books. I came in after a wave that included Tom Feelings and Jerry Pinkney and Walter Dean Myers and Mildred Pitts Walter and others. They were prolific new voices. But back in the day, it seemed like I knew every single illustrator and writer of color and could call them up. The field should not have been that small. Today, there are more creators of color but the percentages of books featuring people of color has apparently diminished despite the wide range of work covering a wide range of topics, being created by a wide range of people of color. The disparity can’t be corrected by people of color. There still exists a mentality that a child will only appreciate a book with someone of his own race on the cover and that is what needs to change.

As a black woman, I think a lot about the lack of black women picture book artists working in our field. Do you have any thoughts on why African American women seemingly aren’t pursuing careers in picturebooks as much as their male counterparts?

We could be at this for days. I have this talk in class every semester. Not just about African American women though…about all women. Here’s my thinking and it is unrefined and preliminary at best: There seem to be a grillion-to-one women-to-men at every children’s book conference and in every class. But the industry is heavily male when it comes to the talent. What I see in class informs my thinking. If you critique a woman she might take your advice, she might reject it. But when challenged or critiqued, some decide it is not working for them, that this may not be the business for them. Men don’t seem to get as easily discouraged. This is a pretty amateur observation based, I think , on one dance I went to in high school where the guys never retreated to a corner or went home if a girl wouldn’t dance. Men seem genetically encoded to pump themselves up and get back in the fray….even if a casual observer would consider them delusional about their gifts. Women need a bit of that chutzpah. What helped me, and the trait I see in the women I know who get published, is a no holds barred passion for the work. I left school with the attitude that this is what I would do. I heard all of the stories about folks who ‘got discovered’. But what I’ve found over time is: male, female, black, white, whatever…you have to throw everything you have at this if you want to do it.8

I could ask many more questions, but I will end with one more. What advice do you have for illustrators working today who are trying to sustain a career as long and successful as yours has been?

It is as huge a cliche as you’ll ever hear: Do what you love. It won’t feel like work. It won’t ever get boring. You won’t ever retire. If, bless you, you one day sell the worldwide film rights to your little picture book and make a grillion dollars, you’ll wake up the next day and still want to tell another story. And it will be fun.

Thank you Pat for all that you do and have done for us puppies!

I certainly would not have made it this far without you and your work.

To see more of Pat Cumming’s work visit her at www.patcummings.com.

You can also find her on facebook.

1. For those of you who want to become book illustrators, a book typically takes six months to a year to illustrate, but as I tell all of my students, it is a marathon, not a sprint. Do your very best work and if that means slowing down a tad to ensure your best work, then by all means, do so. Do be realistic about your working process and let your publisher know well in advance how long it will take you to finish. Tom Feelings’ The Middle Passage is an amazing work of art that transcends the label “picture book” by all accounts. You can see more of his work here. (Fast forward to 31:00 to hear Tom in his own words).

2. I speak to my students often about choosing a partner wisely. Male or female, choosing a partner who respects you and your work is crucial to living a long and artistic life. Being an artist is a long and lonely road for most, and there are times when the going will get tough. You will need people in your life, be it a mate, friend, family member, agent, editor, audience, -heck, even a loyal pet will work, to help build you up and remind you that this is work that needs to be done.

3. YES!!! She’s your queeeeeeen to beeeeee! One of the greatest movies of all time. Eddie Murphy and the Hudlin Brothers made black folk so beautiful in their films.

4. I grew up in a family of educators. My mom was an english teacher before becoming a guidance counselor. I also find it funny that many illustrators and authors that I have met over time were raised by teachers. Oh man, I want to make that a book now.

5. I am so thrilled you saw the talent in me then and helped nurture and support it. I was walking around in the dark back then, reaching for stars that I wouldn’t see. I have students like that now, who are amazing artists and storytellers. I drag many of them into the light, but like you, I can only push so much. At the end of the day, they have to find a way to kick the door in for themselves.

6. Again, marathon, not a sprint.

7. Ha! This is hilarious. There is nothing light and loose about your personality. You are bright and vivid in personality and it shines so clearly in the work that you make. It is stunning work, no matter how you arrived at it. Though, the work you did earlier, was lighter and looser. I bought a copy of My Mama Needs Me a while back and was interested to see how much your work has changed from that book and Just Us Women. It’s not a criticism, just an observation. Your use of color is amazing to me.

8. I have this talk too in all of my classes. I ask my students their thoughts about women in the field, people of color in the field, etc. For African American artists though, I wonder if because there aren’t many historically black universities that offer illustration courses. I am seeing more POC at MICA, where I teach, but the numbers are still pretty low. When I was looking at colleges, I didn’t even consider historically black universities because I didn’t know of any illustrators who were making books that graduated from Howard, Spelman, Florida A&M, etc.. As for women, yes, I see so many more in art school, at SCBWI conferences etc., but I tell my students all the time, they have to stand up and be seen. They have to be persistent, and they have to be super confident. As I said in an interview with Sam Weber earlier this year, “if you don’t know that I’m not awesome, I’m not gon’ tell you I’m not awesome”.